'MetaBirkin' NFT Verdict Is Actually Good For Digital Artists

February 17, 2023

Published in Law360

A Manhattan federal jury found on Feb. 8 that the sale of 100 non-fungible tokens containing artistic renderings of Hermès' world-famous Birkin handbags was a violation of the company's trademark rights.

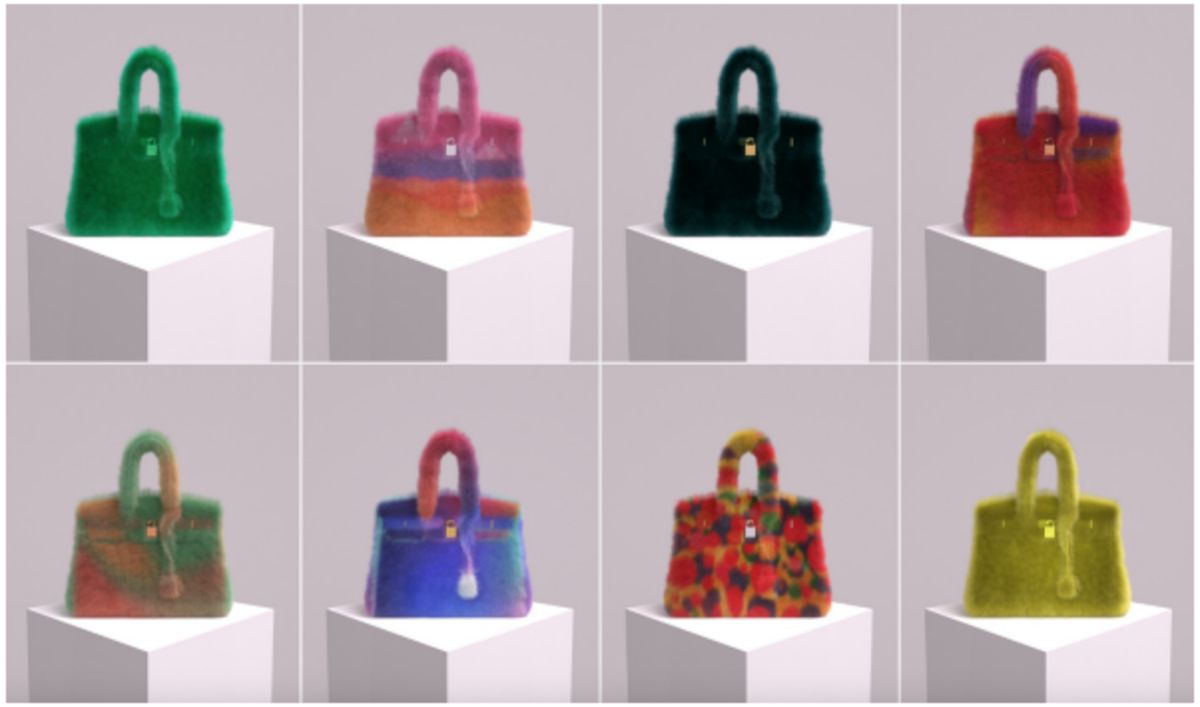

The images, called "MetaBirkins," were not images of physical knockoffs of Birkin handbags, but were instead fanciful digital images of faux fur Birkin bags created by artist Mason Rothschild.

Rothschild's claims to artistic freedom, as enjoyed by Andy Warhol with his famous Campbell's soup can art, were rejected because the jury found that the MetaBirkins were intentionally designed to mislead consumers as to the origin and affiliations of the product.

On Feb. 14, 2023, the court issued a final judgment against Rothschild, stating that "the First Amendment does not bar defendant's liability" and ordering him to pay damages to Hermès.

The New York Times proclaimed that "Rothschild's defeat was a major blow for the NFT market" and the "creator economy," while Rothschild's lawyers said it was a "great day for big brands" and a "terrible day for artists and the First Amendment."

But contrary to these dire claims, the trial is a positive development for digital artists, with, of course, the exception of Rothschild himself.

The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in this case specifically recognized the creative rights of digital artists, particularly art critical of well-known brands, with U.S. District Judge Jed Rakoff ruling that artists can create such art without fear of legal liability so long as it appears to be bona fide and not an intentional effort to confuse customers into believing that the artist's version was made by the brand.

To benefit from this lenient standard, the artist need not prove that their work is actually art, and instead must only show that the work "could constitute a form of artistic expression," according to Judge Rakoff's order denying summary judgment in December.

The legal rulings in the case are highly favorable to artists and should not chill an artist's right to make controversial art.

An NFT is a digital record of ownership, typically recorded on a publicly accessible ledger known as a blockchain. On the blockchain, an NFT functions as "digital deed" representing ownership of a digital asset — here, ownership of a particular MetaBirkin image.

This case was focused on trademark law and not on ownership issues associated with NFTs. No issues concerning NFTs were decided by the jury.

Hermès asserted that the sale of these NFTs, which prominently used the trademarked Birkin name, infringed or diluted its trademarks.

Rothschild countered that the MetaBirkins NFTs were protected by the First Amendment as artistic works that sought to comment on the world's obsession with luxury goods by depicting images of the outrageously expensive bags in a fanciful manner. He also added the digital faux fur to suggest that Hermès' bags violated animal rights protocols.

However, Rothschild also made comments suggesting that money — and not art — was a primary motive in generating the NFTs.

Rothschild observed that "he doesn't think people realize how much you can get away with in art by saying 'in the style of'" and boasted that he was "in the rare position to bully a multi-billion dollar corp[oration]," Judge Rakoff noted in his December order.

According to the judge, Rothschild also said he wanted to make "big money" by

"capital[izing] on the hype," and he referred to himself as "a marketing king," not an artist. And in a text message, he acknowledged that if he used the word "Birkin," instead of

"MetaBirkins," he would be sued.

The case was tried before a jury, with Judge Rakoff giving the jury the standard instruction for finding trademark infringement based on a finding that the alleged infringing good could create a likelihood of confusion as to the origin of the product or as to the parties that endorse or are affiliated with the alleged infringing product.

The court was also mindful that Rothschild's work was art and added a jury instruction that would absolve the artist for trademark infringement if his conduct was viewed as a bona fide effort to create art through commenting on a branded product — much like Warhol.

Judge Rakoff further told the jury in his instructions to assume that Rothschild's work was sufficiently artistic and then to consider his conduct under a heightened standard of showing whether he intentionally sought to confuse consumers into believing that his art was associated with Hermès:

It is undisputed, however, that the MetaBirkins NFTs, including the associated images, are in at least some respects works of artistic expression, such as, for example, in their addition of a total fur covering to the Birkin bag images. Given that, Mr. Rothschild is protected from liability on any of Hermes' claims unless Hermes proves by a preponderance of the evidence that Mr. Rothschild's use of the Birkin mark was not just likely to confuse potential consumers but was intentionally designed to mislead potential consumers into believing that Hermes was associated with Mr. Rothschild's MetaBirkins project. In other words, if Hermes proves that Mr. Rothschild actually intended to confuse potential customers, he has waived any First Amendment protection.

This jury instruction is generous to artists by allowing them the traditional freedom to use art to comment on society.

Liability is only found when the promoter of the art is viewed as disingenuous in claiming the art as a shield to allow otherwise infringing activity.

Notably, the artist need not prove that their work is valuable or even respectable art — only that their art could be seen as a form of artistic expression.

This is a very low standard that any creative artist should easily be able to satisfy. In fact, Judge Rakoff told the jury to simply accept that the MetaBirkins were a protected form of art and removed this issue from the jury's purview.

Next, Judge Rakoff's instructions make clear that the promoter of the digital artwork is fully protected from liability for trademark infringement unless the brand holder proves that the promoter's efforts were intentionally designed to mislead consumers as to product origin, affiliations or endorsements.

In other words, the artist starts the case with the presumption of no liability.

Normally, a brand need only show that there is a likelihood of confusion; it does not have the added burden of showing that the alleged infringer designed its product to intentionally mislead consumers. This will prove to be a difficult burden for brands to establish.

Be Like Warhol, Not Rothschild

If the artist sticks to their script that the brand-inspired art is intended as social commentary or some other artistic purpose, avoiding liability should be a relatively easy task.

This appears to be the approach that Rothschild's idol Andy Warhol took with the Campbell's soup can art. Warhol did not associate his work with the actual soup or create confusion as to whether he was working for Campbell's.

Indeed, Campbell's never sued Warhol because his art was increasing soup sales and not creating any actual confusion between the pop art and the soup maker. In fact, as a thank-you, Campbell's sent him several cases of its now especially famous tomato soup, Warhol's favorite.

However, once the artist goes off script — or worse, as in Rothschild's case — and tries to associate their artwork with the goodwill of the brand or implicitly seeks to create an association with the brand and the art, they will run into significant problems.

Here, Rothschild made many statements that did not focus on his artistic message, but rather on his ability to make money based on the brand's goodwill.

For starters, he chose to feature the word "Birkin" prominently in every aspect of this business and his comments about how much he could get away with in art strongly suggest that Rothschild was attempting to leech off the Birkin brand and goodwill.

Likewise, his reported text message acknowledgment about being aware of the potential for being sued shows a strong consciousness that he was relying on the brand's goodwill and that he intentionally designed his product to benefit from that confusion. Tacking on a "meta" to Birkin did nothing to avoid the association between the images and the brand's handbags.

The overall court rulings strongly endorse the constitutional rights of digital artists to create art without undue fear of trademark infringement.

Like the Warhol model, an artist can use the brand's name and likeness in their art, but they must be careful to avoid any association with the brand. The artist can do so by staying on message about art and promoting their supposed artistic vision, but they should also avoid the brand's market and its likely consumers as sales targets.

Finally, the artist should avoid self-inflicted injuries stemming from bragging about exploitations of the brand's goodwill.

Keep in mind that, according to the jury instructions presented here, the brand must prove with admissible evidence that the artist intentionally designed their product to confuse potential customers as to the origin, affiliation or endorsement between the artwork and the brand. An artist should be able to avoid trademark infringement.

In turn, the brand might take a page from Campbell's legal strategy and find a way to work with the artist, at the same time keeping them from diminishing or tarnishing the brand.

In addition, the ruling did not turn on whether the digital art was sold via an NFT or any other digital vehicle. Thus, the decision has no negative impact on the use of NFTs to sell and promote digital art.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of their employer, its clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.